Decarbonisation is the new buzz word as organisations begin to grapple with net zero objectives to tackle climate change. But what does it actually mean? Research by Ofgem has found that, despite the common use of the term in the energy sector, it is not well understood by consumers, so we’ve put together a short article to help demystify the term.

What is decarbonisation?

Decarbonisation is the process of reducing, or removing, the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions of a country’s economy. Energy use accounts for 73% of global GHG emissions; agriculture accounts for around 12% of global GHG; and changes in land use, such as deforestation, accounts for around 6.5% of global GHG emissions[1]. Since energy use accounts for the largest contribution of GHG emissions, it also offers the greatest opportunity to make a difference to reduce those emissions. Energy use covers transportation, electricity and heat, buildings, manufacturing and construction, fugitive emissions and other fuel combustion.

Carbon and Greenhouse Gases

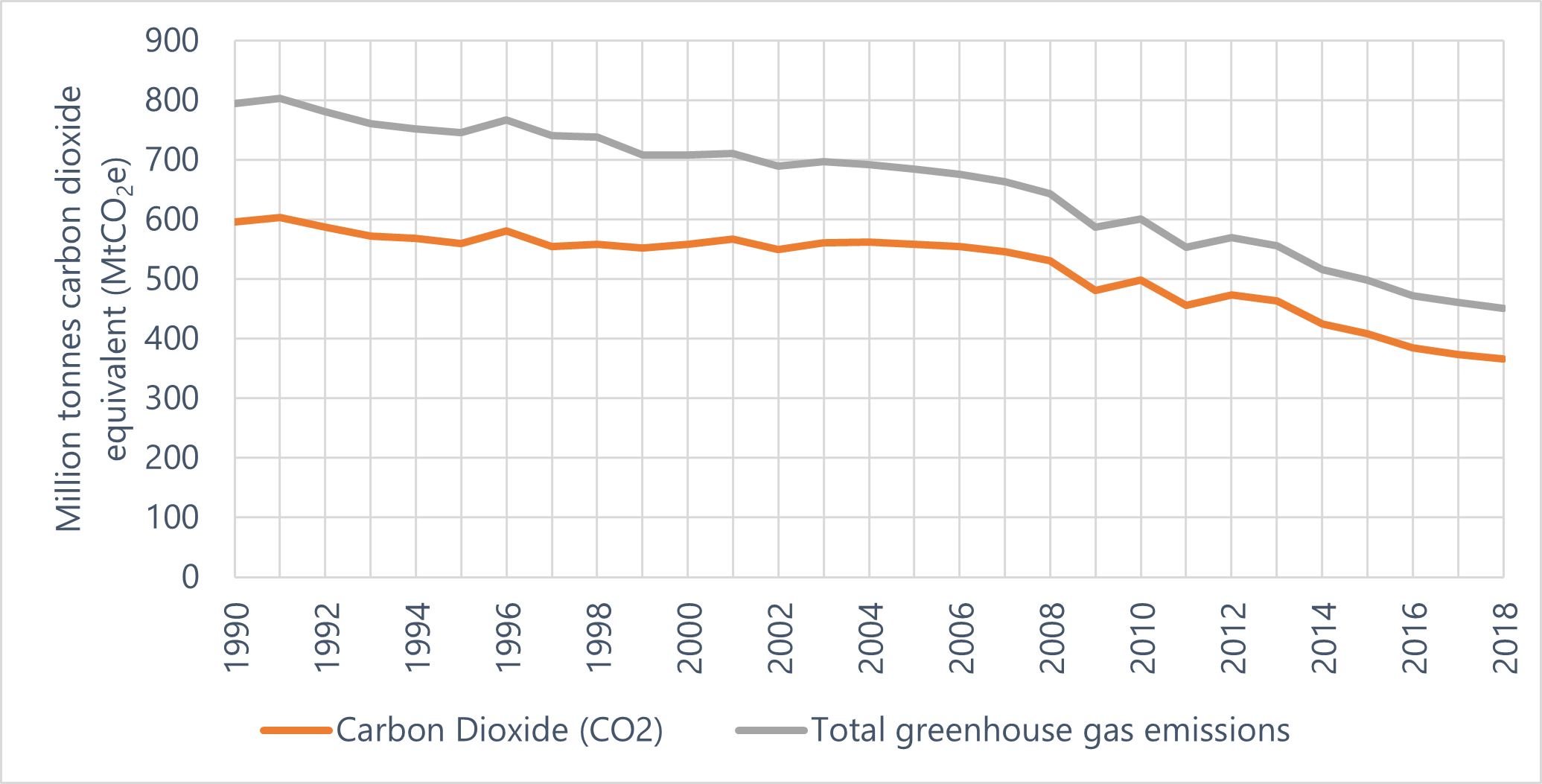

We talk about carbon and GHGs somewhat interchangeably. Within the context of the UK, when we talk about decarbonisation we are actually referring to seven different GHGs, of which carbon dioxide is one. Carbon dioxide, which is emitted as a consequence of burning fossil fuels, accounted for around 75% of the UK’s GHG emissions in 1990. This increased to 81% in 2018.

Why do we need to decarbonise?

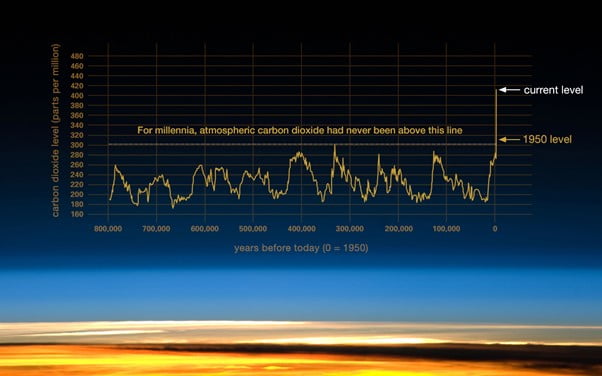

Ancient air bubbles trapped in ice enable us to step back in time and see what Earth’s atmosphere and climate were like in the distant past. They tell us that levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere are higher than they have been at any time in the past 400,000 years.

During ice ages, CO2 levels were around 200 parts per million (ppm), and during the warmer interglacial periods, they hovered around 280 ppm. In 2013, CO2 levels surpassed 400 ppm for the first time in recorded history[2]. This recent relentless rise in CO2 shows a remarkably constant relationship with fossil-fuel burning, and can be well accounted for based on the simple premise that about 60% of fossil-fuel emissions stay in the air.

Today, we stand on the threshold of a new geologic era, which some term the “Anthropocene”, one where the climate is very different to the one our ancestors knew.

If fossil-fuel burning continues at a business-as-usual rate, such that humanity exhausts the reserves over the next few centuries, CO2 will continue to rise to levels of order of 1500 ppm. The atmosphere would then not return to pre-industrial levels even tens of thousands of years into the future. This graph not only conveys the scientific measurements, but it also underscores the fact that humans have a great capacity to change the climate and planet.

Earth’s global average surface temperature in 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest year on record[3].

Continuing the planet’s long-term warming trend, the year’s globally averaged temperature was 1.84 degrees Fahrenheit (1.02 degrees Celsius) warmer than the baseline 1951-1980 mean, according to scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York. 2020 edged out 2016 by a very small amount, within the margin of error of the analysis, making the years effectively tied for the warmest year on record.

Climate hazards are natural events in weather cycles. We’ve always had hurricanes, droughts, wildfires, flooding and high winds. However, we are currently witnessing a scale of destruction and devastation that is on a new scale – and terrifying.

The last year alone has seen a series of devastating climate disasters in various parts of the world, such as Cyclone Idai; deadly heatwaves in India, Pakistan, and Europe; and flooding in south-east Asia. From Mozambique to Bangladesh millions of people have already lost their homes, livelihoods, and loved ones as a result of more dangerous and more frequent extreme weather events.

Source: https://climate.nasa.gov/climate_resources/24/graphic-the-relentless-rise-of-carbon-dioxide/

Why are the weather events so severe?

Simply put, changes in the global climate exacerbate climate hazards and amplify the risk of extreme weather disasters. Increases of air and water temperatures lead to rising sea levels; supercharged storms and higher wind speeds; more intense and prolonged droughts and wildfire seasons; and heavier precipitation and flooding. The evidence is overwhelming and the results devastating:

- The number of climate-related disasters has tripled in the last 30 years.

- Between 2006 and 2016, the rate of global sea-level rise was 2.5 times faster than it was for almost all of the 20th century.

- More than 20 million peopleare forced from their homes by climate change every year.

Four natural global disasters[4]

- In March 2019, Cyclone Idai took the lives of more than 1000 people across Zimbabwe, Malawi and Mozambique in Southern Africa, and it devastated millions more who were left destitute without food or basic services. Lethal landslides took homes and destroyed land, crops and infrastructure. Cyclone Kenneth arrived just six weeks later, sweeping through northern Mozambique, hitting areas where no tropical cyclone has been observed since the satellite era.

- The start of 2020 found Australia in the midst of its worst-ever bushfire season – following on from its hottest year on record which had left soil and fuels exceptionally dry. The fires have burned through more than 10 million hectares, killed at least 28 people, razed entire communities to the ground, taken the homes of thousands of families, and left millions of people affected by a hazardous smoke haze. More than a billion native animals have been killed, and some species and ecosystems may never recover.

- Higher sea temperatures, linked to climate change, have doubled the likelihood of drought in the Horn of Africa region. Severe droughts in 2011, 2017 and 2019 have repeatedly wiped out crops and livestock. Droughts have left 15 million people in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia in need of aid, yet the aid effort is only 35 percent funded. People have been left without the means to put food on their table, and have been forced from their homes. Millions of people are facing acute food and water shortages.

- An El Niño period, supercharged by the climate crisis, has taken Central America’s Dry Corridor into its 6th year of drought. Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua are seeing their typical three-month dry seasons extended to six months or more. Most crops have failed, leaving 3.5 million people, many of whom rely on farming for both food and livelihood, in need of humanitarian assistance, and 2.5 million people food insecure.

Disasters closer to home

Over recent years we have seen warmer and wetter winters; hotter and drier summers; and more frequent and intense weather extremes. This looks set to continue.

The winter of 2013/2014 saw a succession of storms batter the UK, leading to heavy rain and severe flooding across large parts of the country.

The odds of those storms bringing such extreme wet weather were seven times higher than on a planet that wasn’t warming, according to a new analysis by Met Office scientists. The winter of 2013/14 was one of the most exceptional periods of rainfall in England and Wales in at least 248 years. It marked the wettest December and January in the UK as a whole since 1910.

The winter of 2015/2016 saw devastating, record-breaking floods in northwest Britain, with the highest recorded daily rainfall and the highest peak river flows recorded in England.

Remember the severe flooding in winter 2019/2020 and the heat wave of 2018? Met office data shows that that has been a link to Climate Change in the intensity or frequency of warm and cold spells in the UK, with an inconclusive link towards heavier rainfall. Windstorms are also likely to increase in strength and frequency.

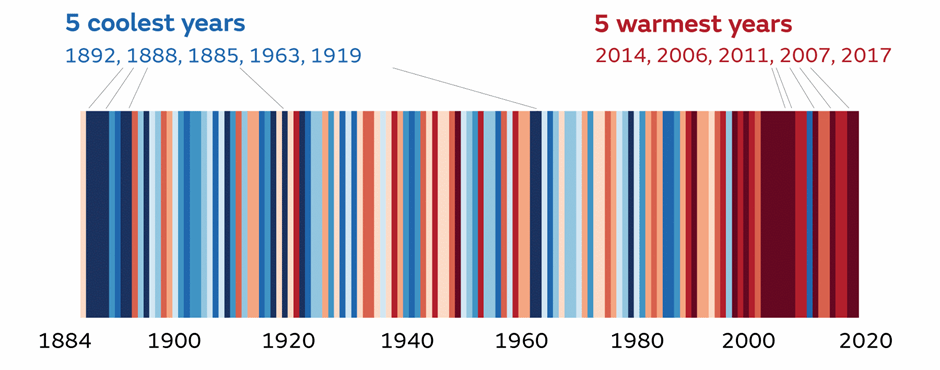

An updated analysis of the annual UK temperature records from the Met Office shows that since 1884 all of the UK’s ten warmest years have occurred since 2002; whereas none of the ten coldest years have occurred since 1963.

These figures are further indications of a changing climate, says the Met Office.

In the latest annual State of the UK Climate report, the Met Office temperature series for the UK has now been extended by 26 years back to 1884. The data has been added as part of ongoing projects to digitise historic weather records.

Dr Mark McCarthy is head of the Met Office’s National Climate Information Centre. Commenting on the extension of the temperature series, he said: “Looking back further into the UK’s weather reveals a very interesting timeline with the top ten warmest years at the most recent end, since 2002. Extending the record back by 26 years from 1910 to 1884 didn’t bring in any new warm years, but it did bring in a number of new cold years, including several that are now within the top ten coldest years.

“Notably, 1892 is the coldest year in the series, when the average temperature was just over seven degrees. By contrast 2014, which was the warmest year in the series, saw an average temperature approaching ten degrees Celsius.”

2018 contained some notable weather events, including the summer heatwave and the ‘Beast from the East’, when a record low daily maximum temperature was recorded on 1 March. Despite this particular cold snap 2018 was, on balance, a warm year and joins the top ten warmest years at number seven. 2018 was the equal-warmest summer for the UK (along with 2006).

Key findings from the State of the UK Climate report:

- 2018 was the third sunniest year in a UK series starting in 1929

- In 2018 the UK received the most significant snowfall since 2010. UK snow events have generally declined since the 1960s

- Over the last decade, summers have been 13% wetter, and winters have been 12% wetter than the period 1961-1990

- Six of the ten wettest years have occurred since 1998 in a UK series stretching back to 1862

- Eight of the ten warmest years for near-coast UK sea-surface temperatures have occurred this century

- Ten named storms affected the UK during 2018

- In 2018, average sea level around the UK was equal highest (with 2015) on record in a series starting in 1901

The State of the UK Climate 2018 report, which is the fifth in a series of annual publications, provides the latest assessment of UK climate trends, variations and extremes. It has been published by Royal Meteorological Society and Wiley in the International Journal of Climatology: a peer-reviewed journal. The dataset on which the report is based makes use of over 100 million historical UK station observations, and is freely available on the CEDA (Centre for Environment Data Analysis) website.

The State of the UK Climate report was supported by the Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme, funded by BEIS and Defra.

Source: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/about-us/press-office/news/weather-and-climate/2019/state-of-the-uk-climate-2018

The Stern review on the economics of climate change is an influential report published in 2006. It was commissioned by Gordon Brown, then UK chancellor of the exchequer, and written by Sir Nicholas Stern, an expert in economics and development who had previously served as the chief economist at the World Bank, among many other roles.

Stern and his team set out to examine “the economic impacts of climate change itself” and “the economics of stabilising greenhouse gases in the atmosphere” – plus the policy challenges of creating a low-carbon economy and managing adaption to a changing climate. The report, which ran to many hundreds of pages, concluded that:

“The evidence shows that ignoring climate change will eventually damage economic growth. Our actions over the coming few decades could create risks of major disruption to economic and social activity, later in this century and in the next, on a scale similar to those associated with the great wars and the economic depression of the first half of the 20th century. And it will be difficult or impossible to reverse these changes. Tackling climate change is the pro-growth strategy for the longer term, and it can be done in a way that does not cap the aspirations for growth of rich or poor countries. The earlier effective action is taken, the less costly it will be.“

More specifically, the review warns that ignoring climate change could reduce global GDP by 20% by the end of the century, and that to avoid this risk the world should spend 1% of global GDP a year, starting immediately.

In 2008, however, Stern announced that his report had underestimated the speed and scale of some serious climate impacts and increased his recommendation for expenditure on emissions reductions to 2% of global GDP. Nonetheless, by Stern’s analysis, ignoring climate change is still many times more expensive than fixing it.

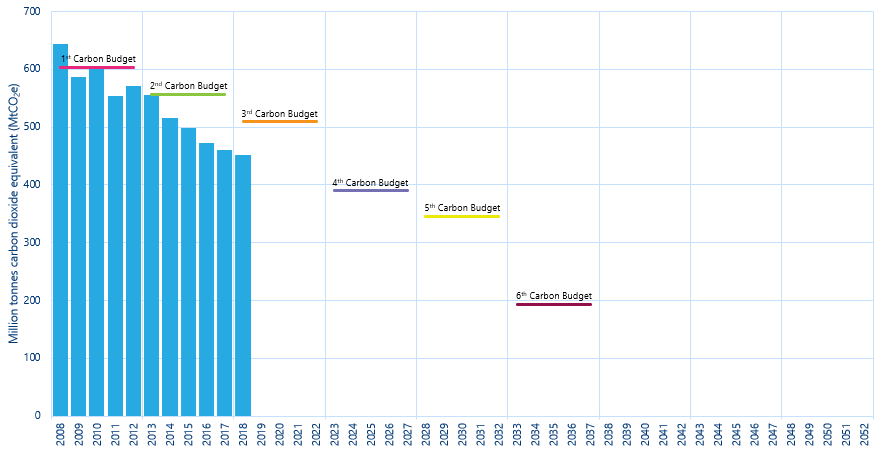

The Climate Change Act was passed in the UK in November 2008 with an overwhelming majority across political parties. It sets out emission reduction targets that the UK must comply with legally. It represents the first global legally binding climate change mitigation target set by a country.

The Act committed the UK to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050, compared to 1990 levels. However, this target was made more ambitious in 2019 when the UK became the first major economy to commit to a ‘net zero’ target. The new target requires the UK to bring all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

The Committee on Climate Change (see below) has reported that the first and second carbon budget were met and the UK is on track to meet the third (2018–22), but is not on track to meet the fourth (2023–27) or fifth (2028–32) budgets.

In June 2019, parliament passed legislation requiring the government to reduce the UK’s net emissions of greenhouse gases by 100% relative to 1990 levels by 2050.[1] Doing so would make the UK a ‘net zero’ emitter.

A sixth budget was signed into law in April 2021 and commits the UK to reduce emissions by 78% by 2035. This is consistent with the size of reduction needed to meet our Paris Agreement commitments to limit global temperature increases by well below 2oC and make efforts to cap at 1.5oC. It is also the first time that international aviation and shipping is formally included.

Source: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-the-2008-climate-change-act/

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-enshrines-new-target-in-law-to-slash-emissions-by-78-by-2035

Looking forward, carbon budgets up to 2037 are now signed into law. At present, we are off-track for hitting these targets which call for a 51% reduction by 2025, 57% by 2030 and 78% by 2035.

Source: https://www.theccc.org.uk/about/our-expertise/advice-on-reducing-the-uks-emissions/

What is Net Zero carbon?

Net zero refers to achieving a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. There are two different routes to achieving net zero, which work in tandem: reducing existing emissions and actively removing greenhouse gases.

A gross-zero target would mean reducing all emissions to zero. This is not realistic, so instead the net-zero target recognises that there will be some emissions but that these need to be fully offset, predominantly through natural carbon sinks such as oceans and forests. (In the future, it may be possible to use artificial carbon sinks to increase carbon removal, research into these technologies is ongoing.)

When the amount of carbon emissions produced are cancelled out by the amount removed, the UK will be a net-zero emitter. The lower the emissions, the easier this becomes.

In Summary

It is critical that everybody plays their part and takes action now to mitigate climate change. Zenergi is committed to supporting organisations to do just that. The path to Net Zero Carbon is a journey not a race, and Zenergi’s technical division is well placed to help you assess and benchmark your consumption and discover a strategic plan for your organisation to achieve net zero.

Our Decarbonisation Services include:

Carbon Management Plans and Net Zero Carbon

We can help you on the journey to Net Zero and make sustainability a core part of your CSR.

Low Carbon Mechanical and Electrical (M&E) Design

We’re experts in the design and project management of practical, cost-saving low carbon building solutions that deliver long-term value through reduced ongoing energy and maintenance costs.

Energy Surveying and Auditing

Typically, energy audits and surveys offer a return on investment of less than one year, achieved through quick wins and awareness training.

Water Surveying and Auditing

We can identify and implement water use reduction. Our water surveys typically deliver 20% savings, recovering the survey costs within a few months

Carbon Legislation Compliance

ESOS, SECR, CCAs

If you would like to understand more about preparing your own decarbonisation plan to help set your strategy for the journey to net zero carbon, contact us.

Sources:

[1] Source: https://www.wri.org/insights/4-charts-explain-greenhouse-gas-emissions-countries-and-sectors

[2] Source: https://climate.nasa.gov/news/916/for-first-time-earths-single-day-co2-tops-400-ppm/

[3] Source: https://climate.nasa.gov/climate_resources/139/video-global-warming-from-1880-to-2020/

[4] Source: https://www.oxfam.org/en/5-natural-disasters-beg-climate-action